- Home

- Alicia D. Williams

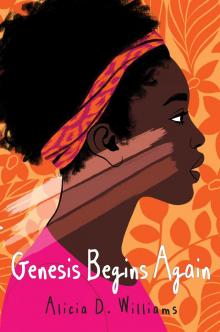

Genesis Begins Again Page 9

Genesis Begins Again Read online

Page 9

“Ow, Mama!”

“Stop moving. You wanna go to school all marked up?”

“No,” I say, gingerly touching the burnt spot.

“Then be still.” Mama places the comb back on the burner and puts a little grease on my hair for sheen.

“Why can’t we get a flat iron?” I say, trying not to squirm, braced for another potential nick. “This is abuse.”

Mama ignores me, as usual. The comb’s now hot again. She takes it and pulls it through my hair. The grease melts, runs to my scalp and singes me, and I jump clear out the seat. The kitchen reeks with the smell of burnt hair.

“Genesis, you should be used to this by now!”

“No one should ever get used to this, Mama,” I tell her, rubbing the new burnt spot.

“Sit back down here; we don’t have all night.” Mama brushes my hand away and parts another small section of hair. “Gosh, your hair’s so thick.”

“That’s why you should let me have a relaxer.”

“We’ve been through this before.”

“Seriously, Mama, I’m the only girl in America who doesn’t have one. How many thirteen-year-olds you know still have to have their mama press their hair? No one owns a hot comb anymore! Or even knows what it is! And you’ve seen the kids at this new school! Everybody’s hair is straight.” I hope Mama won’t see Nia; she wouldn’t help my case at all.

“Hold your ear.” Mama cocks my head to the side. As her fingers grasp the tiny hairs behind my ear, I feel my neck and shoulders and thigh and butt muscles all tensing up. Don’t burn me, don’t burn me, I chant in my head. “Be still,” Mama chides. She blows on the comb as she gets the iron insanely close to my scalp.

When she places the comb back down, I relax and start my argument again. “Everybody and their mama have weaves or relaxers or braids, or something. I’m too old for a stupid blowout and press.”

“How many times do I have to tell you, Genesis?”

Mama only has to tell me once, but it’ll never matter. I’ll always ask, and she’ll always answer with “You wanna get a relaxer and lose your hair again?”

I’ll say “no” because I never told Mama that the bald spots were actually because I used Nair hair-removing cream to take out the unrelaxed nappy hair once the new-growth started growing in. I’ll say “no” because I’m still ashamed that I wanted the coily part gone so badly that I didn’t even stop to consider what that stupid cream would do. I’ll say “no” because I remember when my hair fell out in patches and Mama drove herself nuts questioning why, and the beautician insisted that it was the relaxer and cut my hair almost to my ears, and I cried and cried and cried. Now I wonder if I should tell her and maybe she’d let me try a relaxer again.

Mama doesn’t need a relaxer. Her hair’s naturally straight and long, and sometimes she curls it in big, round ringlets. It’s so pretty that total strangers comment on it. This one time, we were at the Laundromat and someone asked if she was Alicia Keys. What a stupid question. Why in the world would Alicia Keys be washing her clothes in a public laundry—in Detroit?

Mama pushes my head back down. “Gotta get the kitchen.”

The kitchen is at the nape of the neck. Why grown folks call it that I have no idea. Maybe because it’s messy, like a kitchen can get? Plus, it’s the worst part to straighten and the first part to kink back up.

I silently pray for Mama not to burn me. “Owww!” God doesn’t listen.

“Sorry,” says Mama. “Well, if having two little burns is the worst that happens today, it’s not such a bad day.”

If only she knew.

eleven

When people say stuff like: “What else can go wrong?” well, that usually translates to: “Waaaiit for it. . . .” It only takes about five minutes before my burns seem like a treat, ’cause that’s when Dad gets home.

Please, God, let me have enough shine on my hair.

“What up, doe?” Split shift, my big toe. Dad’s been hanging out with his crew, still stuck in Detroit mode, using the official greeting. He positions himself at the kitchen entrance and watches us. A sweat towel hangs from his shoulder.

He comes over and tries to kiss Mama on the cheek. She turns her face away, waves the hot comb in the air. “Been drinking, haven’t you? Sweating like you’ve been working harder than a fireman on Devil’s Night.”

Devil’s Night? Whoa. Mama’s throwin’ some serious shade. The night before Halloween, prankster kids and arsonists light fires all over the city. It’s gotten so bad that the firemen get so hot and exhausted that sometimes they just let the old abandoned houses burn. Hmph, he might be sweating like it, but Daddy ain’t been working that hard.

Mama’s snap bounces right off him, though, because he stands by the stove, grinning away. She sets the comb back on the burner, and I can tell pressure is building by the way she rubs her forehead. And Dad cheeses even harder. “Wanna know why?” he says, a little slurry.

Mama folds her arms tight, furious.

“I’m celebrating,” he tells her, thrusting his hands up like he’s shooting a basket. “And I went out with Chico and ’em . . . to celebrate my new job.”

“You got the job?” I turn to Mama repeating, “He got the job!”

Dad nods. Mama takes up the hot comb and presses it against the towel. It sizzles. And I swear Dad shifts around, as if he’s the one getting his hair straightened.

“Dad, you really got the promotion? For real, for real?” I ask, only because he doesn’t look as happy as I’d be looking if it happened to me. Shoot, I’d be dancing all over the place.

“Ain’t that what I said?” Dad says, now sounding edgy. “Ain’t you happy, Sharon?”

Mama takes her time rearranging the hot comb, grease, and towel on the stove before answering. “Seems to me that celebrating with family would’ve been your priority.”

“Priority? That all you got to say?” Dad says, drying his face with his sweat towel.

Is that all she’s got to say? Boy, is he begging for an argument or what?

“Congratulations,” Mama finally says, but it comes out sounding more like Con. Grad. You. Lay. Shuns. Then she wipes her hands roughly on the towel.

“Thanks, but you don’t sound too thrilled,” he says, stepping away from the stove.

I pipe in with a cheerier-sounding congrats, and add a: “You did it, Dad!”

“Thanks, Gen,” he says, going back to grin-mode. “See, at least my baby girl is happy—”

“So.” Mama cuts my props off. Dad was giving me props. “You got the same hours? How much more money is it? And what happened to AA? Those meetings approve of your drinking?” Mama rattles off questions without taking a breath.

“Whoa, whoa, why you third-degreeing me?” Dad now turns his attention to me, not answering any of Mama’s questions. “Chubby Cheeks, you think I’m wrong for going out too?”

Now I’m the one folding my arms, ’cause my chorus bad mood was turned good, and now it’s quickly swinging back to bad.

Mama pushes my head down, undoes another poof, and gets back to pulling the hot comb through my hair. I can feel the tension in her arms, and I’m back to chanting, Don’t burn me. Dad stares, weaving, near unnoticeably, but weaving. And nobody mentions the fact that he still hasn’t answered Mama’s questions.

“Ain’t you glad you never have to press your hair, Sharon?” he asks, wiping at his forehead again.

Here we go.

“Emory.” Mama points the comb right at him. “We happy for you and all, but nobody’s in the mood for your drunk foolishness tonight.”

And I now understand Sophia’s need for the library—I wish I could escape there this instant. Except Sophia doesn’t seek peace because of a drunken dad.

“I’m just sayin’. . . .” Dad goes to the refrigerator. “Anyone ever say you look like your mama, Gen-Gen? I can’t remember.”

No one ever says I look like Mama, and he knows it. But I do think of something. “I got h

er smile,” I say, reminding him of his own words from a week ago. He acts like he doesn’t hear me as he closes the fridge door without getting anything out and leans against it, not saying a word.

“You just don’t know when to quit, do you?” Mama’s voice rises from level one to level two—the tread lightly voice. Truth is, I kinda hope she lays into him, makes him regret drinking. She pulls the comb through the final poof, then draws my hair back into a ponytail and tells me to get ready for bed.

“Baby girl, look at you,” Dad says, “hair as straight as an Indian’s.” Indian. I sigh. Every Black girl I know, at one point or another, stands with friends on the playground and claims to have Cherokee in her family. Somebody’s always trying to prove they’re connected to beauty. When Dad comes over and stretches his hand out toward my head, I know that he knows I’m no different.

I pop up and duck past him. “They’re called Native Americans, not Indians,” I say, avoiding his eyes. Same eyes as mine. People who see us together say, “Emory, it looks like you spit that child out.”

“Emory—enough! You’re not about to stir up this”—Mama swishes her hand in the air—“mess. You promised me ‘Things’ll be different’ and ‘I’ll stop drinking.’ ” She’s dipping into level three, her voice isn’t raised, but she’s starting to blow up.

“Sharon, relax. Ain’t we been waiting for this—our big break? That’s got to be worth one celebration drink.”

Mama’s screwing the cap on the grease, tight, like she means to strangle it.

“I know what one drink looks like,” Mama argues. “One drink doesn’t make you mean. And right now, you’re mean, and you’re not about to be mean to Genesis!”

This is my cue to slink down the hall to my room and close the door. I bet Sophia doesn’t have to go through stuff like this.

“Genesis?” Dad calls out. “You know I’m just playing with you, right?”

Even though I pull my pillow over my head, I still hear him. He always has to say something. Always. And he isn’t just playing. I also bet Sophia’s Dad doesn’t play like this.

When Mama’s fussing quiets, I climb out of bed and put my ear to the door. Nothing. I stuff my blanket around the bottom real good to make sure light doesn’t escape. Then I turn the light on and stand in front of the dresser with my eyes closed. When I open them, Dad’s face appears with a twisted smile. Look at you, hair as straight as an Indian’s.

I pull out my brush. Years of hair, lint, grease, and fantasies are stuck deep down in the bristles. Childish dreams of looking like Cinderella, Belle, and Pocahontas are trapped in there. I undo my stubby ponytail, and brush my hair one hundred times like Rapunzel. Except I don’t want hair long enough to trip over. I want hair like Mama’s. So I pray over and over, “Lord, turn it good. . . . Lord, please turn it good. . . .” After a gazillion strokes, my hair hangs stiff and straight, and it still looks nothing like Mama’s. So I slick my edges down and tie my scarf on real tight.

I take out the list from my sock drawer and put a star by #64: Because her dad’s right, no one says she looks like her mama.

If people did, then Mama wouldn’t have to torture me. Dad would lay eyes on me and smile like he does at Mama. Then he would croon to both of us as we ride in his car with the windows down and our hair—soft, soft hair—blowing in the wind.

twelve

“Genesis, didn’t I say cut that TV off?”

“No, you asked if I was done with my homework.” I press the power button on the remote and the TV goes black.

“Don’t get smart; it’s the same thing.” Mama’s already freshly showered from a day’s work. “As a matter of fact, bring your homework to the kitchen table and work on it in here.”

“Why?”

“Because I said so.”

“Said so” is technically not an answer, but still I gather my books and drop them on the table. Even though Dad got the promotion, Mama’s still annoyed that he came home drunk last night. And, I’m still annoyed about his teasing. And because he’s not here, we only have each other to let out puffs of madness to.

Mama darts about the kitchen, whipping up dinner. When she’s done, she fixes our plates. I slide my books to the floor, get the silverware, and Mama finally sits down. She takes a breath before asking, “How was school?” as if nothing’s bothering her at all.

“Fine,” I say, as if nothing’s bothering me, either. “I’ve made a few friends, Sophia and Troy, he’s my math tutor—”

Mom suddenly looks alarmed. “You have a math tutor? Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because it’s not a big deal, they’re on a different math level at this school is all.”

“So, a boy, huh?” Mama smiles. Big. And this is the reason why I don’t talk about school much.

“A tutor, who happens to be a boy.” I make swirls in my mashed potatoes. “That’s all.”

“Okay, okay.” She holds both hands up, surrendering.

“Dad still at work?” I mutter.

Mama glances at her watch. “I think so. He says he’s in training, so his hours are longer. He’s supposed to go to the AA meeting tonight, I believe.”

I notice with sudden dread a few folded-up moving boxes stuffed between the refrigerator and wall. She’s not saving those boxes for us to move again, is she? But no, Dad’s new job will make everything all work out. Right? I pinch off a piece of my chicken, but can’t eat it. I hate those ever-ready moving boxes. I wonder if we’ll ever not have to have them ready.

Then out of the blue Mama says, “Genesis, we need to talk.”

Whoa, did she just read my mind about the boxes? I’m not sure I even want to hear what’s coming: “We need to talk” is never good.

“I’ve been thinking . . . things may not change with your daddy.” There’s worry in her eyes as she studies me, and then she totally throws a curveball. “What’s clear to me is that my mother’s right . . . about me getting my degree, and I need a better paying job to take care of you—us. So—I’ve started applying to different companies.” Then, even though it’s just us two, she lowers her voice and says, “And I’ve been saving money, for school. I’m praying not to have to use it for anything else.”

Mama’s never mentioned going back to school, and she’s never ever admitted that Grandma’s right. And I hope Mama’s only meaning is that Grandma’s right about her education and a better job. ’Cause it sounds awfully like Mama’s planning to leave Dad, but that can’t be the case, could it?

She’s staring at me. Oh. She wants me to respond.

“Genesis, I have to do this. . . . I need to do this,” she presses.

“That’s cool, you should totally go for it,” I assure her. “I could help out around here, do more chores and stuff. Hey, we can even do homework together, right here at the table.”

“Thank you, honey,” Mama says, her face lighting up. “And, Genesis, let’s just . . . let’s just keep this between us, okay?”

I nod. We all have secrets, but Mama’s aren’t like Dad’s—secretly smoking in the house or sneaking off to the casinos. Or mine, singing in the mirror. All of a sudden I wonder if Billie Holiday ever sang in front of the mirror.

“Mama?” I say. “You heard of Billie Holiday, right?”

“Lady Day, of course! Why?”

“My teacher let me borrow her CD.”

“Yeah? I didn’t grow up on her music, but I like it. There’s an old movie about her life, Lady Sings the Blues.” Mama goes on describing the movie. She tells me that Billie Holiday was addicted to drugs and her husband kept trying to help her beat it. Then Mama describes how the doctors strapped her in a straitjacket. Yikes! And that’s who Mrs. Hill pegs me like?

“We should rent it,” Mama says, getting up to fill her water glass. “I swear I drink more simply because it comes straight from the refrigerator’s door.” She takes a sip before continuing. “That Billie, she had a hard life, a real hard life.”

Sure sounds like it! Th

en it hits me. Billie Holiday’s husband must be to Billie Holiday what Mama and I are to Dad. Did Billie’s husband ever get tired of helping her? Mama always accepts Dad’s promises and stays, but now that she’s planning to go back to school, does it mean his apologies are wearing thin? So I ask point-blank if she’d ever leave him.

My question catches her off guard because she quickly says, “Huh?” When I used to say “huh,” she’d say, If you can “huh,” you can hear. But I ask her again, anyway.

Then she starts with a dragged out, “Wellllll, Gen . . . it is a possibility . . . if things don’t change.”

Mama must’ve been doing some heavy-duty thinking. And Dad’s stupid antics haven’t helped his cause. But we can’t move yet. We just can’t. Yeah, chorus sucked, but . . . I like it here.

My conversation with Mama was deep, so you already know that when it’s time for me to sleep, my brain won’t shut off. I get out of bed, turn on my CD player and slide Billie Holiday’s silver disk inside. And I really listen. Her voice . . . her voice is incredible. It swings up to the high note so smoothly—how does she do that? And then it hovers over the piano chords gently, gently. She sounds sad. But something else, too. Hopeful. I want to belt out Billie’s lyrics. But Billie doesn’t belt. She lets her pain ooze out slow. I wonder what caused her “sickness.” I pick up the CD cover, and Billie’s eyes are lonely, as if she wants someone to notice.

I notice, Billie.

The next day at school, Billie’s songs keep humming in my brain. It’s like I have my own soundtrack; in language arts I wanted solitude and by the time I got to PE, heartache was waiting on the track. So, when my last class is done, I stop at the library to find a book to match my miserable mood. As if it’s my destiny, I spy a hardcover biography about . . . Lady Day! Sitting right there on the shelf. This is way too cool of a coincidence to keep to myself. Who else to tell other than Sophia?

But she isn’t at her locker. I backtrack to the library; she’s not there, either. Not in Ms. Luctenburg’s class, the locker room, the office—where the heck is she? Just as I’ve convinced myself that she left without me, I decide to check the one place I didn’t. The bathrooms. Each one—by our locker and homeroom—is empty. Sophia’s gone. It’s probably my fault for taking so long in the first place.

Genesis Begins Again

Genesis Begins Again