- Home

- Alicia D. Williams

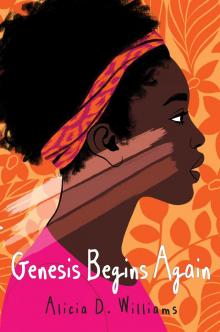

Genesis Begins Again Page 15

Genesis Begins Again Read online

Page 15

“I’m gonna bomb it. I just know it,” I say, frustrated, now totally getting Sophia’s major freak-out about her test.

“You’re not going to bomb it,” Troy assures me. “This is about C work already. Study for the next few days and by Friday you’ll kill the test, trust me.” He’s packing up his books, and looks, I don’t know, uneasy? I bet it’s because of those guys from the hall, and I just have to ask again.

“So,” I start, “those guys I saw you with. What’s up with them?”

Troy flashes me a look. “What do you mean?”

“They didn’t look legit, you know.” I want to be there for him, but don’t want to pry too much. So I throw my hands up in an I’mma-back-off sort of way. “I’ll leave it alone if you want.”

“Naw, it’s fine. They just want some notes,” Troy says, waving away any concerns I might have. Or so he thinks, because I know and he knows darn well that those dudes wanted more than notes. I know their type; they want to pass without doing the work. But if Troy’s not ready to talk about it—like I’d been about “falling down the stairs”—then I’m straight with just knowing he’s okay.

After school, Sophia and I hang out on the bleachers to catch a few minutes of softball practice. I tell her that I can’t stay too long because even though nothing much happens out here in suburbia, Mama’ll have a fit if she beats me home and doesn’t know where I am. And when she starts to balk, I remind her that I can’t be making my mama mad since she’s letting me come over Saturday.

“Being a pitcher is hard, a lot of pressure,” Sophia mutters. Her eyes are now on the pitcher who just took her place on the mound. “Being at bat, that’s tough too.”

“You play?” What all is Sophia into besides reading, I suddenly wonder.

“Not anymore,” she says, nodding hard as the pitcher fires a perfect pitch. Before I can pose another question, she’s telling me that she played as a kid, but things got too hectic. “So my mother said we should scale back on some of my extracurriculars.”

“I never have any extras,” I start to say, but then I remember Mrs. Hill. “But you know what? My chorus teacher thinks I should audition for the show.”

Sophia turns to me. “Seriously? Are you going to do it?” She breaks into a genuinely happy smile.

“I’m not sure.” I debate delving into it, but talking about it might help me figure out if I do want to do it, or not. “Here’s the thing, Sophe, I’m not really down for putting myself out there like that. I just feel like, I don’t know, I’ll get ripped apart or something.”

She nods. “Yeah, like when I played softball. If the team lost, there was someone always wanting to point a finger. I wish those fingers didn’t bother me,” she says, squinting back out at the field.

“Yeah, those stinkin’ pointer fingers,” I say, wondering how it was that some people were not able to care about them. And why weren’t we two of them?

The rest of the week, Dad’s been coming home every night. Mama’s leaving must’ve scared him straight because he ain’t even been drunk. Good thing, too, because I’m already pulling at my hair, worrying about math. On Wednesday, Sophia tries to prep me for Saturday’s dinner at her house, but my mind is on solving equations without solutions. Thursday, I miss our library time because Troy took pity on me and gave me an extra tutoring session. And Friday—well, it’s lucky that I have any hair left.

My number two pencil is between my fingers, ready. I glance over at Troy, and he mouths, You got this. I cross my fingers, wishing us both good luck. Once Mr. Benjamin gives us permission to begin, I’m off. Pretty soon I’m whizzing through the test, determining x, y, z, simplifying fractions, and wondering why I was even nervous in the first place. And then there’s this question: Find the missing number so the equation has no solution. Whaaa? Isn’t the point to have a solution? This has got to be a trick question. Skip. I’m back rocking and rolling, and solving equations using diagrams. And wouldn’t you know it, Mr. B. sneaks in a word problem. Yes, a word problem!

One of your friends is heading north for a holiday and the other friend is heading south. If their destinations are 1,029 miles apart and one car is traveling at forty-five miles per hour and the other car is traveling at fifty-three miles per hour, how many hours before the two cars pass each other?

This makes no sense at all. Like seriously, if Sophia leaves heading north for, say, Christmas, she ain’t gonna make it. Hello—have you seen our winters? And let’s say Troy’s going south? How would I know if he’s going forty-five miles per hour or fifty-three? And they’re both going for a holiday vacation? Score! So, Sophia’s traveling north, Troy south—wait just a minute, if she’s going north and he’s going south, how in the heck are they supposed to cross paths?

Mr. Benjamin calls time. I wait until after everyone turns in their tests before approaching him. Mr. B. asks how I think I did and I answer, “Fine.”

“If you have a few minutes, can you grade it?” I ask, adding a sweet “please.” Mr. B. checks his watch and informs me that he has only a few minutes to spare. I stand at my desk as he pulls out an ink pen and furiously begins marking and scribbling. That’s a lot of scribbles. I might as well pack up and go to the lower class. Finally, Mr. B. waves me up front, and I swear his face is as dark as the Grim Reaper’s.

Mr. B. hands me my paper. I knew it. Just knew it. A doggone 76 percent. Wait. Seventy-six? I passed. I passed! I really passed!

“Thank you!” I say, holding up my test. “Thank you,” I say, kissing it. “Thank you,” I just about scream, as I fly out of the room.

“Genesis?” Troy’s propped up against the lockers, waiting. “Is everything okay?”

“I PASSED!” And he hugs me. Me and my big green 76 percent.

twenty

On Saturday, Mama escorts me over to Sophia’s. On her street, the houses are even bigger than on mine. One thing about these Farmington Hills folks, they sure do like to keep their curtains open. You can see all through their houses. It’s like they’re not even afraid of thieves scoping out places to rob.

I hook my arm around Mama’s, both of us still feeling real proud about my math test and . . . drum roll please . . . that she ordered a college catalog. We pass fresh cut lawns and neatly trimmed bushes, and she points to different flowers that are blooming. “And those are ferns, but I want to plant some of those blue ones, periwinkles. Aren’t they pretty?” Out here folks hire landscapers. They’re always in some yard cutting and mulching. By some miracle, if we were to actually stay here, Mama’ll need a whole lot of planting time just to keep up.

Mama reads the numbers on the mailboxes. “What’s the address again?”

“93488.”

“The even side is over there. So, eighty-four, six . . . this must be her house here.”

“Whoa!” It’s big, real big. There’re four tall white columns lined across the front porch. Potted trees that twist up like the tops of soft ice-cream cones sit on each side of the front double door.

“Do I look okay?” I say, stepping in front of her.

“Yes, you look great. Wait, is Sophia a boy?” she teases.

I elbow her, grinning, as we climb the steps and ring the bell. The doors are glass, with intricate flower designs etched in them.

“You call me if you want to leave before nine.” Mama squeezes my arm, as if she’s sending me off to my first day of kindergarten.

The door opens. A woman with dark hair and glasses greets us. “Well, hello!” She has the exact same brown eyes as Sophia, so it must be her mother. “Come in, come in. Sophia!”

We step into the foyer, onto a red rug with black swirls and gold leaves. A pot that holds umbrellas sits in the corner and a big WELCOME TO OUR HOME sign hangs on the wall. “Sophia’s told us all about you. You must be Mrs. Anderson. I’m Elissa.” Mama tells Mrs. Papageorgiou to call her Sharon, which she does. Mrs. Papageorgiou leads us through a second set of doors and into a huge living room. Shimmery gold curtains are

suspended from the ceiling all the way down to the ground. The couches and chairs are white, their legs etched with ornate antique-ish designs. They even have long mirrors framed like pictures and medium-size chandeliers—six to be exact.

Fancy.

Mama must be in shock too, because all she manages to do is smile.

“Sophia!” Mrs. Papageorgiou calls out again. “I hope you brought your appetite, Genesis.” It’s then that I smell spices. I can’t put my finger on which. All I know is that it smells good.

Sophia comes running into the room and thumps my shoulder. “Hey, you!”

Mrs. Papageorgiou introduces Sophia to Mama, offering, “Would you like to join us for dinner? There’s plenty.”

Mama’s telling her, “No, thank you,” and Mrs. Papageorgiou informs Mama that she, herself, will personally bring me safely back home. Sophia takes my arm, and I give Mama one last wave before I’m whisked away.

“This is going to be so much fun,” Sophia exclaims.

She guides me through rooms, introducing me to her father, three of her brothers, three younger cousins, and two uncles. Everyone talks so fast that I can hardly understand them. The kitchen is a frenzy of food preparation: pots clang, steam rises, and spoons stir. Several women, who Sophia points out as her aunts and grandmother, chop, stir, and taste, fingers full of food while laughing and talking.

“Hey, everybody,” Sophia announces. “This is my friend Genesis.” There’s a chorus of waves, nods, and hi’s.

“Who?” Her grandmother leans forward in her chair where she’s rolling meat into little balls. “What did she say?”

“I said,” Sophia repeats, louder, “this is my friend Genesis.”

“Genesis? Like in the Bible?”

“Yes, Mom, that’s what she said,” says Mrs. Papageorgiou, who’s joined us. Then she addresses me, saying, “You might be thinking this is a lot of food, but in our family, we show our love by feeding you.”

“It’s true,” Sophia says. “She’ll keep offering, but at one point you’ll have to say ‘I know you love me, but no’ or you’ll bust. She doesn’t realize her love leads to high cholesterol.”

“Sophia!” says Mrs. Papageorgiou, play-smacking her.

Sophia grabs my elbow and leads me around the gleaming marble island. It would blow Dad’s mind compared to ours. Sophia says, “We call our aunts ‘Thea.’ Just call my grandmother ‘Yiayia,’ that’ll be fine.” Then Sophia stops in front of the kitchen cabinets, which aren’t really cabinets at all but a wall with glass doors, the dishes displayed like pieces of art. “Here, take these.” She hands me several plates, not just regular plates, but breakable ones with elegant designs, the kind that Grandma keeps in her china cabinet and never uses. Then she pulls out glasses and I follow her to the dining room. She sets the glasses down on a long, polished wooden table. Next, I put down the plates.

“No, that’s not how it goes,” Sophia says, correcting me. “The plates have to be exactly in the center, just like this, and glasses to the right. You have to measure it with your hand.” Sophia determines the distance, slides the glass a millimeter, and studies it again.

“Sorry. I didn’t realize it was that serious. We don’t follow any particular dining rules at my house.” I feel kind of embarrassed.

“No worries, it just has to be a certain way.” Sophia goes and gets a box of silverware. Silverware in a box? Each piece has its own little holder. Yikes! Sophia notices my look. “Yeah, my yiayia’s nutty about the silverware—it’s from Greece and hand-forged. So they have to be handled gently and placed perfectly.” She now starts removing the utensils piece by piece, laying them down just so, then readjusting them, too.

Mrs. Papageorgiou breezes in with a tray of food. “Sophia, it doesn’t matter, remember?”

“But—” Sophia starts, but then the theas swoop in, each also bearing a tray, and proceed to load so much food onto the table that it looks like Thanksgiving. The holidays at my house never have this much food, or people. Sophia and I go back and forth for more plates and glasses. The theas rotate in and out with serving tools and more trays, and pretty soon the aromas summon all the relatives into the dining room. The food smells so good that I worry I might actually drool.

Sophia slides out a chair. “Sit near me. I always sit near my baba—my dad.” Mr. Papageorgiou parades in with the uncles, goes straight to Sophia, and kisses her forehead. He has a mustache like Dad, but he looks friendly, like a TV dad. I can’t remember the last time Dad kissed me on my forehead.

We all squeeze into chairs at the dining room table, and once everyone’s settled, Sophia’s baba prays—in Greek. Then Yiayia says another grace—in Greek. As heads are bowed, I notice all the whiteness surrounding me. A month ago, I’d never even been around white people, except in passing at the mall. I sit on my hands, suddenly afraid to reach for the same spoon as someone else in case they notice the difference too. Yiayia finishes the prayer, and they all draw an invisible cross from their head to their chests and across. Amen.

“Genesis, try the souvlaki, which is chicken on a stick,” suggests Mr. Papageorgiou. “My wife makes the best.” Mrs. Papageorgiou’s cheeks flush happily as she tells me that that’s why he married her.

Sophia points out all the dishes—I only recognize olives and feta cheese. “These green things are grape leaves stuffed with beef and rice, dolmades,” she explains. “There’s lamb, too. Here, try some.” She holds the serving fork out to me, but I hesitate. I wish the bleach bath lightened me. “C’mon, try some—it’s good.”

Slowly I take the fork, waiting for all eyes to turn my way. They don’t. Everybody’s busy filling their own plates. So I relax and take some lamb and then go for it like everyone else, making sure to take some of Mrs. Papageorgiou’s souvlaki. Sophia piles up her plate too. Except she’s extremely careful about making sure the food doesn’t touch. When an olive rolls toward a meatball, she quickly flicks it back over to the other olives. And guess what? Mr. Papageorgiou has set up his plate the same way, nothing touching.

Conversations erupt across the table. “Then she goes in the market and says . . .” “Ha! Is that so?” “It is so! When we were growing up in the village, things were very different!” They talk in both English and Greek. They wave their forks, slap the table, and fill their plates with more food. Then Sophia asks her yiayia to tell me the story about the goats chasing her every time she went to milk them, which she does, and everyone starts interjecting their two cents, slowing down the story for me to hear the best parts.

We laugh and eat. And Mr. Papageorgiou was right, the souvlaki is delicious. Even the spinach wrapped in a flaky pastry called spa . . . spa . . . I whisper to Sophia and ask for the name again of these tasty things. “Spanakopita,” she says. Like everyone else, I go for seconds, while Sophia’s still on the first round, eating one thing at a time. Really, really slowly.

When dinner’s over, Sophia shows me her bedroom. “I get my own room because I’m the only girl,” she says, swinging her door open.

“Wow, everything’s so—”

“So what?” Sophia asks quickly.

“Neat. Mine’s a disaster!” Butterflies dangle from the ceiling. There’s a shelf full of stuffed animals, probably kept from since she was a kid. Everything’s perfectly placed. “How long have you lived here? Your whole life?”

“Yeah,” Sophia says, as if that’s a stupid question.

Her younger cousins, two little boys and a girl, run in. “Hey, get out of here!” Sophia shouts. “Don’t touch my things.” They jump on her, wrestle with her, and twist her hair. They eye me curiously as well, probably wondering if it’s safe to jump on me, too.

“Okay, out now.” As he leaves, one of the boys deliberately shoves the notebooks on her desk so the perfectly aligned pile slides to one side. “Hey, I told you about touching my stuff!” Sophia yells.

“Fat head!” the boy yells back, and they all run out of the room.

“Finally.�

�� Sophia locks her door. Then she centers her rug and brushes out the wrinkles on her bed.

“Now I see why you go to the library,” I say with a laugh. “Wish I had a lock on my door too.”

“Privacy’s the best.” Sophia restacks her notebooks.

“Yep, the best,” I agree. “You’ve got a cool room. What’re all these trophies? I didn’t know you did anything besides read and, well, play softball.” I go to her shelf for a closer look.

“You think I only sit on my butt with a book in my hand?” Sophia laughs. “My mom used to enroll me in everything. Classical piano, fencing, tap, gymnastics, you name it. There’s a lot of pressure being the only girl.”

I take it all in. Must be real nice to take classes like fencing and gymnastics. All I ever got to do was play kickball, checkers, and make art at some youth program. Must be cool to win a trophy with your name on it. “But, hey, you get your own room.”

“Yeah, how about that trade-off?” She laughs again. “It’s probably not a big deal to you because you’ve never had to share—you being an only child.”

There’s no way I’m admitting to sharing rooms with my mama, and sometimes with both Mama and Dad. So I shift the conversation. “Hey, I just thought of something—you can audition for the talent show too! You can play the piano while Troy plays his violin.”

“No way. That’s not my thing, either.”

I pick up a picture that’s sitting on her nightstand. Sophia’s with her dad at a carnival. She holds a bag of cotton candy, and he’s squeezing her like he’s trying to get all her juice out. They both have gigantic smiles.

“Uhm, so—it makes me nervous when people touch my stuff.” Sophia says it nicely, but she also takes the photo and places it back neatly.

Okay. A little weird. But I say sorry. “I wasn’t going to break it.”

“Sophia?” Mrs. Papageorgiou calls through the door. Sophia goes and unlocks it, and Mrs. P. pokes her head in. “You girls need anything?”

Genesis Begins Again

Genesis Begins Again